Sexton Blake

Sexton Blake was the poor man’s Sherlock Holmes, created in 1893, just six years after the original. His exploits were chronicled until 1978, accounting for about 4,000 stories by about 200 authors, in comic strips, annuals, magazines, booklets, novellas, and movies, beginning in Victorian England, moving through the World Wars (he was present at Hitler’s death in the bunker), and concluding during the era of mods and rockers in London. I was introduced to the series in August 1961 at which time two 64-page booklets were being published monthly.

My father, a civil engineer whose work took him to various parts of India (we lived in Bombay), would pick up the latest booklets at the A.H. Wheeler bookstalls which graced most railway stations (just the right length for a couple of train journeys), and dump them in our godown (store room) on his return. I was 11 at the time, reading children’s stories, primarily by Enid Blyton, the biggest seller of children’s books to this day and (at the time) the third richest woman in England following the Queen (I forget who was second)—stories about plucky British kids thwarting Nazis, smugglers, kidnappers, jewel thieves, et cetera.

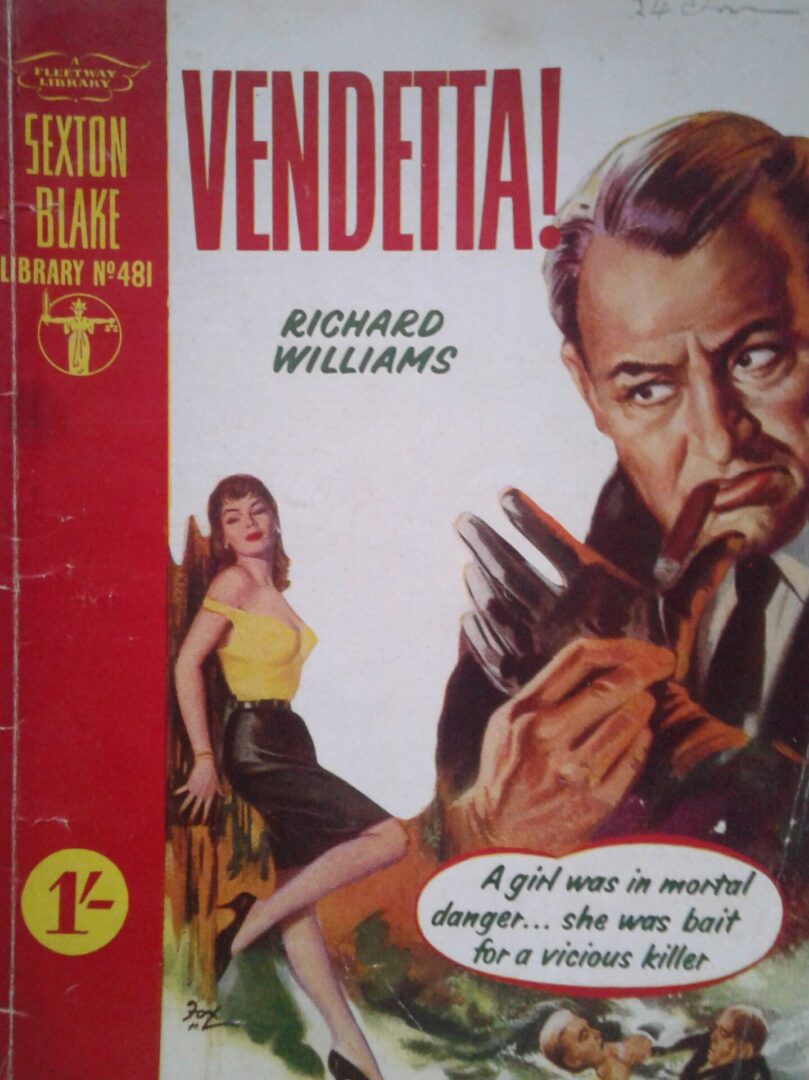

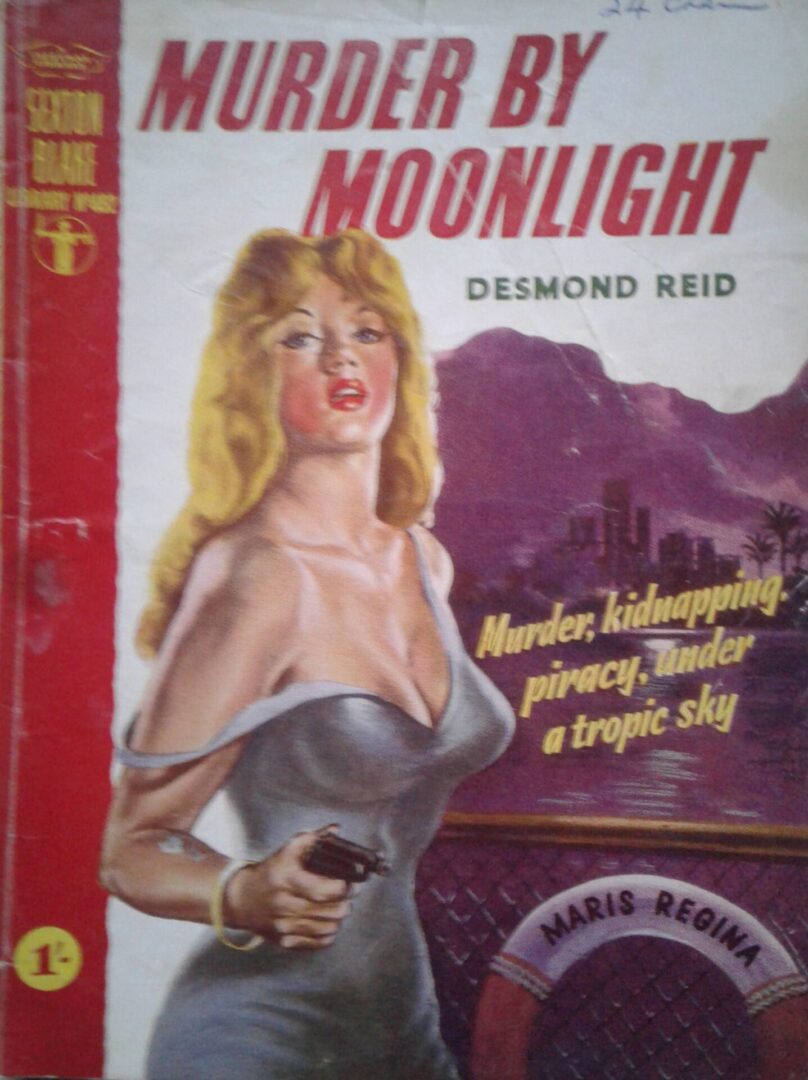

Once, rummaging through old newspapers, I came across Vendetta by Richard Williams and, enticed by the cover, started to read. Marion Lang, Sexton Blake’s receptionist, crosses the hallway from her flat to borrow shampoo from a friend, only to find the door to her friend’s flat open. Hearing the shower running in the bathroom, she advances, calling her friend by name, only to find her hanging from a noose, and as the body turns she sees a knife embedded in its back! I was mesmerized! and took the booklet and its companion for the month (Murder by Moonlight by Desmond Reid) to my bedroom to read uninterrupted to the end.

Shortly afterward, talking it over with Anand Mehta (friend and neighbor), I remarked this might be a fine way to make a living, fabricating stories for which you got paid. Anand was younger by a couple of years, but wiser by a couple of decades. It’s not so easy, he said, to which I replied I was sure I could do it and the following week wrote my first fiction, a 10-page Sexton Blake story in which one of his adversaries sent him a grandfather clock, supposedly a gift from a fan, the ticktock of the clock covering the ticktock of a hidden time-bomb. My second was an 18-page SB story, after which I wrote stories modeled on whatever I happened to be reading (Tarzan stories, sf stories, thrillers, even a potboiler about witches stirring an immortality brew inspired by Macbeth).

It was a couple of decades later that I discovered my own voice (I was 32), finally writing a story no one else could have written, recognizing how prescient Anand had been, perhaps beyond even his own understanding. Six years later I published my first novel, The Memory of Elephants, realizing in the process that becoming a novelist was far more difficult than becoming an architect (as my father had wished) or a psychologist or market analyst (careers with which I had flirted), because there is no beaten track to becoming a novelist as there is to those professions. Each novelist has to find her own way, whether by being in the right place at the right time, in a continual state of readiness for the opportune moment, making the opportune moment for herself, cultivating influential acquaintances (even, it wouldn’t surprise me, sleeping with the right people).

The images below are of the two booklets from our godown (repurchased on ebay a few years ago). I’ve now read Vendetta 3-4 times. It is pulp fiction par excellence and blankets me in a nostalgic glow during each reading, a respite between bouts with more profound fiction—as do the Blyton books to which I also return periodically, as innocent as the Blakes are not.