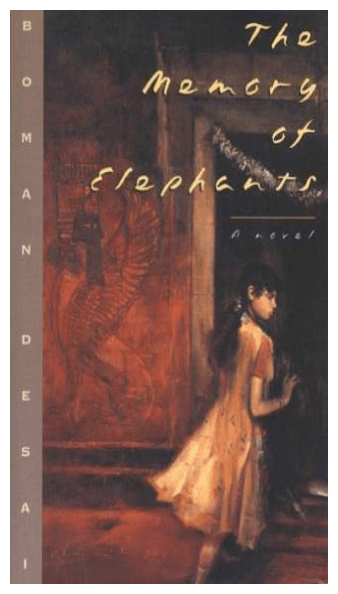

THE MEMORY OF ELEPHANTS

When Homi Seervai, a whiz kid from Bombay, is dumped by his first love in Aquihana, Pennsylvania, he invents the Memoscan, a machine designed to scan his brain to make a record of its memories. Isolating the memory traces covering his time with his inamorata, he sets the Memoscan on a repeat cycle to relive continually the most ecstatic hours of his life. Unfortunately, the machine goes haywire, dipping into his Collective Unconscious, the Memory of Mankind, including his own racial, familial, and ancestral memories. Seeing the dead and the living juxtaposed in a jigsaw of history and biography, he imagines he is going crazy—but, instead, as he comes to realize, he is only beginning to live, his first love no more than a flicker in the panorama of possibilities that beckon him into new life.

A big book with a baroque design.... By an interweaving of narrative voices, a brilliant picture is drawn not only of individuals ... but of a whole upper-class Indian family.

Adam Lively (Punch)

India comes to life with great vividness and humor. Added to that are rewarding insights into the alien wisdom of exiles. The writing is never dull and the observations are acute. You sense a generosity of spirit in Desai's way of looking at the world and at people.

Elon Salmon (Yorkshire Post)

The charm of The Memory of Elephants lies in the easy naturalness with which writer Boman Desai describes life in a middle class Parsi family over three generations. It is neither pretentious nor a parody as such narratives often turn out to be.

Coomi Kapoor (The Hindustan Times)

Fantastical though the framework, the book is neither a fantasy nor science fiction but a vividly realistic presentation of three generations of Parsis. A variety of strikingly life-like characters, drawn with a warm feeling of kinship, yet with much humor, and often with a penetrating satirical observation, give the novel a vibrant sense of reality.... A very readable and highly promising first novel.

Homai Shroff (The Indian Post)

An accomplished first novel, an ingenious approach to the family saga form. The author has brought off exactly what he set out to do.

Janice Elliott (Afternoon Despatch)

Desai's style is fluid and he weaves together a tapestry of Parsi history well. His keen mind, his elephantine memory (which accounts for the title), and his sharp humour make for enjoyable reading.

Glenn Rogers (Afternoon Despatch)

The Memory of Elephants illuminates a fascinating kaleidoscope of collective and family history. The strengths and eccentricities of the Parsis are revealed through a rich range of characters.

Maria Couto (Third World Quarterly)

In the final image [the narrator] beholds his Parsee ancestors showering their blessings on him. His triumph in juxtaposing the past and the present leads to self-knowledge. He expresses his joy thus: I had done it; I had brought them all together in one place at one time, made a whole of all the scattered pieces. This brilliant image captures the essence of the narrative. He succeeds in "connecting" the past and the present.

V. L. V. N. Narendra Kumar (Kakatiya Journal of English Studies)

The book is as evocative as a box of old snapshots.... The characterizations are vibrant, and the writing has so much drive that, once started, it is almost impossible to leave the book unfinished.

Roshni (The Statesman Literary Supplement, India)

BACKGROUND

When I was 25, it was a very good year. Let me revise that: it was the best of years, it was the worst of years. The summer brought about my most ardent love affair, and the fall, my most traumatic breakup. I fell into a downward spiral–until, taking a course in psychology, I learned about Dr. Wilder Graves Penfield, who had conducted experiments to cure epilepsy. He peeled back the scalps of his patients to probe their naked brains with an electrode, asking as he probed if they felt a fit was imminent. Once he had determined the part of the brain corresponding to a fit, he excised that part of the brain, resulting in complete cures in 50% of the cases, appreciable cures in another 25%, and no cure at all in the last 25%–but no harm either to the patients.

What interested me more than anything was a side-effect of the probe. One woman said she felt as if she were giving birth to her first child all over again. It was more than a feeling: she could describe the room and its inhabitants in the minutest detail as if she were reliving the experience rather than recalling it. Another patient said he could hear the march from Aida when the doctor administered the probe, recalling times when his uncle had played the opera on a stack of 78 rpm records. When the doctor removed the probe, the music stopped. After a number of similar episodes, Dr. Penfield realized he was igniting memory traces within the brain–and I realized that the summer with my inamorata was hardly lost. It was imprinted on my brain. All I had to do was probe my naked brain with an electrode to relive my summer as often as I pleased.

I didn't do that, I didn't have the expertise, but I did have the expertise to conjure a character who had the expertise–and that is what I did. A whiz kid from Bombay loses his virginity to an artist's model in Aquihana, Pennsylvania, only to have her move on once she's notched her bedpost. He invents the memoscan, isolates the convolution in his brain which carries the memory of his singular night, and trains the machine to scan the convolution repeatedly. He knows he will die. Under the influence of the machine, in the grip of the memory, he can neither eat nor drink and will very likely succumb to dehydration in 3-4 days. Either that or the convolution containing the memory trace will cut deeper into his brain with each successive recall until his brain splits in two. But the narrator doesn't think of it as dying as much as living with his love forever.

Unfortunately (or fortunately), the memoscan (which uses a non-intrusive laser instead of Dr. Penfield's electrode) goes haywire. Instead of focusing on the convolution of the rhapsodic night, it slips into the protagonist's Collective Unconscious, the repository of not only personal memories, but familial and ancestral—and universal memory of mankind—bringing us to the memory of elephants, a metaphor for long-term memory, also the frame of the novel within which three generations of a family saga are played out—but I’ll leave the reader to discover the rest for herself.

EXCERPTS

One

Let me be clear: It wasn’t a movie as much as a single scene, a single scene which I had played repeatedly through the memoscan—at first, and for countless times, successfully, to its conclusion—but, increasingly, the memory disintegrated into hallucinations. Yes, hallucinations. There was no other explanation. Back in the room, I saw naked Candace; back outside, camelbacked Arabs; back and forth, back and forth, Candace and Arabs, Arabs and Candace, both hostilely glaring at me. When the images began to merge, my command finally slipped and I surrendered to the madness. The lips of her vagina grew larger, more wrinkled, grey, an elephant’s trunk and tusks emerged from the folds, elephant ears sprouted like wings on her back. I think that was when I started to scream.

What was happening? A vagina was flying on elephant ears, dragging trunk and tusks behind. Worse, I saw the dead (Bapaiji, Granny, Dad) and the living (Mom, Jalu Masi, Sohrab Uncle, Soli Mama, Rusi, Zarine—Myself!) as if they were acting out the scenes of their lives by my bedside. Worst of all, I saw armies, hordes and phalanxes of warriors, Arabs and Iranis, on foot, horseback, camelback, elephantback, engaged in battle, showers of descending arrows, a constant swarm of adverse activity as might be witnessed when rival ant colonies or galaxies collide. The fantastic merged with the real, the ancient with the modern, naked Candace, airborne on elephant ears, mounted on an elephant’s trunk and tusks, split into a hundred similar images, and the flight of Candace angels soared to meet squadrons of flying monkeys approaching from the distance. The landscape was littered with rhinestone jackets, gold ballet slippers, blue miniskirts, and red panties, all to the accompaniment of a relentless atonal symphony. No wonder I felt in terror of imminent insanity.

Two

They were not far when they heard Dhunmai call. Adi threw everything into his sack and jumped into the tree, Bapaiji on his heels. They didn’t mind being found together, but didn’t want to give Dhunmai the satisfaction of finding them. Too late they realized they’d left one of Adi’s whittling knives on the ground.

Behind Bapaiji, in the thick foliage, hung the tails of three monkeys. She would have ignored them; there were hundreds of monkeys in the trees, tails hanging like furry brown ribbons; but not this time. She grabbed all three tails and yanked—hard. The idyll of the forest was slashed as if by lightning: the monkeys shrieked oop-oop-oop-oop, setting other monkeys shrieking, birds screaming, a wolf howling in the distance as if it were night; and woven into their screams, as brilliantly as the centerpiece of a peacock’s fantail, was Dhunmai’s screech as she turned and ran. The monkeys continued to shriek, oop-oop-OOP-OOP-OOP-OOP!!, baring their teeth, whooping around Bapaiji and Adi as if the trees had suddenly grown too hot to touch. Bapaiji bared her own teeth, whooping back. Adi laughed so hard he fell out of the tree; when Bapaiji reached to catch him he pulled her down with him; the fall knocked the air out of them and they choked, unable to stop laughing.

Three

The summer came to an ugly end: Penny, descending the schoolbus, flaxen hair flying as she turned her head for a final (too prophetic) goodbye, flashing her last big happy sweet last lover’s smile before the rush across the street to meet Erica, her English speaking ayah whom she called Nanny; a screech, a thud, a scream, Miss Bean (responsible for the children on the bus) shouting, “Do not look. Nobody is to look out of the window.”

How does a six year old cope with the loss of his sweetheart? He puts himself in quarantine, he lowers his resistance, he searches out toxins as if they were grail, he dreams of a reunitement (pupal angels cocooned in a Hansel and Gretal heaven). In the two years that followed I contracted mumps, jaundice, chicken pox, typhoid, two kinds of measles, three kinds of flu; I underwent a second tonsillectomy, an appendectomy; I had yet to run through cholera, small pox, tuberculosis, and whooping cough, but something I read and someone I met so exposed the selfindulgence of my quarantine that even the most benighted eyes (mine) began to see.