THE PIANO ALBUM

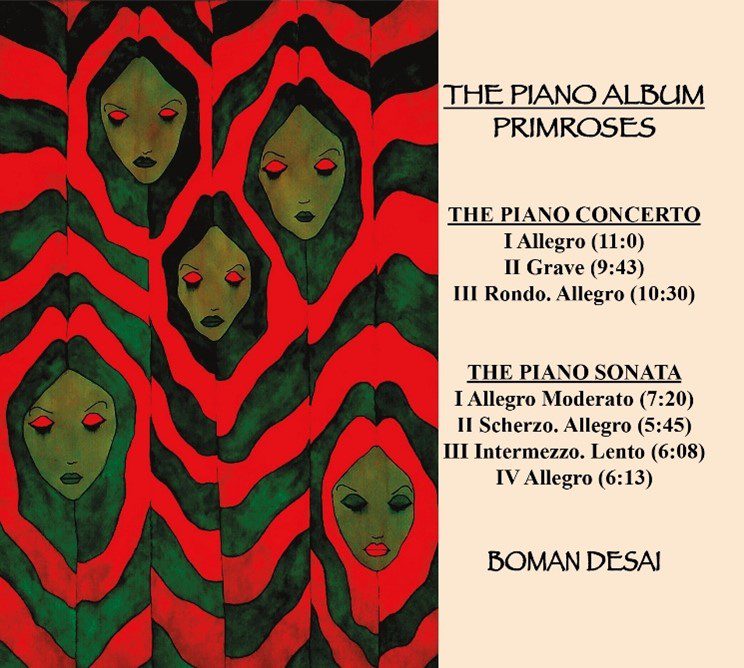

Please click on any of the three images to hear different snippets from the Concerto.

PIANO CONCERTO

First Movement (Allegro): Sonata form is the standard format for the first movement of a concerto. It opens with an Exposition (two themes, first in the tonic, second in the dominant), follows with a Development (running through as many keys in as many combinations of the themes as the composer desires), and concludes with a Recapitulation (restatement of the Exposition, both themes in the tonic, usually with some variation). An Introduction is not necessary, but in this instance gets proceedings off to a roaring start. Thundering timpani followed by galloping triplets on piano, are punctuated by tuttis from the orchestra. Winds and strings join the gallop, only to have the ensemble reined shortly to a trot by three chords in strings, lowering the temperature, setting the stage for the Exposition (statement of the first theme). The long-breathed melody contrasts a four-note phrase with a rising three-note phrase, stated first in a cadenza by the piano, followed by the orchestra. A furious transitionary passage (loud set of descending scales) leads the movement into the second theme—a pretty melody, meandering up and down the keyboard, peppered by flights from flutes and clarinets, then bassoons and brass, leading to the other instruments leapfrogging one another into the Development.

The Development opens with loud angry chords from the piano and a growling vibrato from the bass plying the first theme, only to be pushed back by winds plying the second theme. Various combinations of the themes follow. Amid the chaos, the first theme is heard in the form of a drunken waltz followed by the second played in quiet dissonant fourths, before reaching the Recapitulation (a truncated Exposition), and sliding seamlessly into the second movement (the last note of the first movement is the first note of the second movement).

The two themes were derived from two songs I wrote: “The Biggest Kid” (1991) and “Dandelion” (mid-1970s). “The Biggest Kid” was structured on “La Vien Rose,” a song I have long loved and wanted to emulate. Both songs open with melodies descending three tiers before going separate ways, but lyrically they could not be more different. “Rose” sees life through rose-tinted glasses, “Kid” through the eyes of a woman whose blinkers have been removed, her lover revealed for the merry-go-round that he is, coming around regularly, only to disappear as regularly, and she calls him the biggest kid, telling him not to bother coming around anymore.

“Dandelion,” from which I developed the second theme, had nonsensical lyrics, comparing people to flowers. It was a good idea badly developed (I knew neither flowers nor people well enough to make it work). Fortunately, a good melody doesn’t need lyrics.

Second Movement (Grave): The second movement flows directly from the first, structured in an ABABA format. A brief introduction, I, opens the piece and each segment is divided by transitional measures, t. A more accurate thumbprint would be IA1t1B1t2A2t3B2t4A3. I derived the entire movement from a song I wrote in the late Seventies called “Night Light,” verses providing melody for the A segments, choruses for the B. Melodies are not easy to come by and I originally recycled the same melodies for the second movement of my second Violin Sonata. The song calls attention to moonlight pouring through a window, leaving the bedroom shimmering and misty, sharp edges blunted—more importantly, softening the lines on the face of the woman sleeping in the songwriter’s arms. I won’t say too much, but the stately approach of the first A leads to a rambunctious episode (the first B), finding the lovers at the peak of their affair. A2 and B2 modulate the movement tenderly toward A3, the most nocturnal (and nocturne-like) of the variations, answering the question asked by Antonio Carlos Jobim in his song, “How Insensitive”: What can you say when a love affair is over? a question better answered with music than words.

I wrote a number of songs from the 1960s-1990s, in each of which I attempted to do something different. I was intrigued by Jethro Tull’s “Living in the Past” because it was written in 5/4 time (unusual for a pop song) and I wanted to do the same with one of my songs. The verses of the song, “Night Light,” are in 5/4 time, the choruses in 6/4, but early one morning, drifting from a dream state into the light of dawn, I heard the song in 7/4 time and couldn’t resist discovering how the rest might develop. This movement is the consequence of that curiosity.

The progression of chords in the B section was inspired by another Jethro Tull song, “From a Dead Beat to an Old Greaser.” An apparently neverending series of chords bears a poignant melody (not unlike the chords of Beethoven’s “Moonlight”). I used a different set of chords, but I would not have discovered my set had I not listened closely to (in love with) the Tull song.

Third Movement (Rondo: Allegro): The third movement is structured ABACABA. The A segment (the primary theme) derives from another song I wrote in the Seventies, “Will We Still Be Lovers (when the romance ends)?” wondering about the state of a romance once the bloom is off the rose. It is heard in five different incarnations through the rondo, separated by the episodes of the B and C segments among various transitional measures, t, concluding with a Coda. The detailed thumbprint is closer to A1t1A2t2B1B2B3A3t3Ct4A4t5B4B5t6A5Coda.

The episodes (B and C segments) are new melodies, created for the rondo. The C segment is the jewel in this crown—and A4 (the primary theme ridden at a brisk canter on the piano spurred by nips and flurries from strings and winds) the most ingratiating. The Coda opens with solo piano, soon fortified by the rest of the orchestra as the ensemble gushes toward an elemental conclusion.

The primary melody, as I said, had been with me since the Seventies, but it was then more poignant, befitting its lyric. I first heard it dressed in the colors of the concerto after listening to the rondo of Brahms’s Second Piano concerto (the fourth movement). Hearing Brahms at perhaps his most whimsical prompted a similarly whimsical treatment of my own melody. I intended to follow Brahms’s structure from A to Z, but the work soon chose to go its own way and I had no choice but to follow my own inspiration instead.

A friend sent me a link to the score of the Third Piano Concerto by Einojuhani Rautavaara (1928-2016), a Finnish composer, because I had expressed a kind of despair about composing piano runs. The Rautavaara is gorgeous, but I wasn’t influenced by the runs as much as a segment in which he played major chords simultaneously with their parallel minors. You will hear the influence in the transition t4. It sounds dissonant, but gets increasingly consonant with familiarity.

PIANO SONATA

First Movement (Allegro moderato): As with a concerto, so with a sonata: the first movement is generally Sonata form, opening with an Exposition (two themes, first in tonic, second in dominant), following with a Development (running through as many keys and permutations as the composer desires), and concluding with a Recapitulation (restatement of Exposition, themes in the tonic).

The first movement opens with the first theme, a joyous lilting long-breathed melody. The second theme, no less joyous, is slower, shorter, and bouncier. The Development juggles both themes before entering the Recapitulation—but the most unusual segment is the Coda, not a requisite for such a movement, but harking back to the first theme, the jollity turning poignant, ending the movement on a pensive (not a triumphant) note—in part because the next movement (the Scherzo) begins triumphantly and the quiet conclusion provides a more suitable springboard.

The melodies for both themes came from a song I wrote during the Seventies, “Single Women,” first theme from the verse, second from the bridge. I was young enough then to think I understood people, in this instance single women. Fortunately, lyrics become extraneous in an adaptation of this nature and melodies remain valuable.

Second Movement (Scherzo: Allegro): The second movement of a sonata is generally slow, but considering the first movement of this sonata ended quietly I wanted a lively beginning for the second. Scherzos have an ABA format, dynamic A’s sandwiching a tranquil B (the Trio). Strictly speaking, this is not a Scherzo. It only approximates the ABA format, the dynamic A section is immediately apparent, as is the tranquil B—but, instead of returning to A, the A and B sections caress and condole each other—until close to the end when A, the Scherzo melody, appears again in all its original strength to conclude on three staccato notes.

The melody was taken from another song I wrote in the Seventies, “Girls of the City,” the verse providing the Scherzo melody, the bridge the Trio. Also, as with the earlier song, the lyric became extraneous, the melody invaluable.

Third Movement (Intermezzo: Lento): Intermezzo has more than one meaning, but is perhaps most simply defined as a lull, providing a contrast, between two movements of a larger piece (such as a sonata or symphony). I chose an Intermezzo to take the place of the slow movement—but in third place instead of the usual second (as mentioned above).

This Intermezzo comprises 7 sections, opening slowly, quietly, soon stepping up the pace to a cantor for the second section and whipping it into a gallop for the third—before bringing it back to the trot of the first section and following again with a cantor and gallop, the gallop repeated with a different harmony before being reined again to a stop.

The melody came from yet another song from the Seventies, “I Go to Pieces,” a fitting follow-up to “Single Women” and “Girls of the City,” a Don Juan reduced to his just desserts.

Fourth Movement (Allegro): By definition, a Theme & Variations provides a theme to be followed by variations of the theme. The best-known theme for such variations is Paganini’s. Schumann, Liszt, Brahms, Rachmaninoff, and Lutoslawski (among others), all adopted Paganini’s theme for variations of their own. I chose to open with a few introductory measures modeled on Paganini’s rhythm, a tip of my hat to the fountainhead.

The movement proper begins with a theme I adapted from the verse-melody of yet another song from the Seventies, “Crazy Mary” (the first of my songs to incorporate a diminished chord), another melody I had recycled previously for the Scherzo movement of my first Violin Sonata. I followed the theme with 11 variations, some in the styles of other composers. The 3rd & 4th variations showcase a Bachian counterpoint (left and right hands exchange melodies going from the 3rd to the 4th variation). The 5th variation is modeled on one of Schumann’s Symphonic Variations, the 7th on the first movement of Mozart’s Piano Sonata in A, and the 11th and last movement loosely modeled on Dvorak.

The concluding variations accelerate toward the last which is a hop, skip, and a dance toward the coda—concluding, as did the Scherzo, with 3 staccato notes. I wanted the last variations to move propulsively to the end, much like the last of Brahms’s Handel Variations (I make no pretensions to being in Brahms’s league)—or, to provide a more recent reference, the pacing of the songs on side two of Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.