THE ELEPHANT GRAVEYARD

A Moby Dick for Elephants

Myrtle Bailey’s death in the circus ring clouds the lives of 5 people and one elephant: Hazel (her daughter, chief elephant handler); Brown E (a clown, once Hazel’s lover); Dinty (her husband, once a contortionist); Jonas Frank (proprietor of the circus); Spike (her son, ghost narrator of the story); and Hero (blackest elephant in the world, oiled to blackness to grab attention during the dreary years of the Depression). Their fortunes are tied to those of the Blues, a black family: widowed mother Maudine; Royale (favored son, hair of ginger, skin of peach); Elbo (born elbowfirst); and Prize (for Surprise, Elbo’s unexpected twin who came tumbling after). Amid the sawdust and spangles, the jitters and jangle, erupt scenes both horrific and exotic: a king cobra loose in a Chicago penthouse; a black boy trampled to death in a Toledo citysquare; slaves riddled with smallpox left on West African riverbanks awaiting crocodiles; a white elephant in musth (testosterone overdrive); a striptease on elephantback. Multiple thrills and zaniness mingle with meditations on slavery, circusing, the afterlife, and the ivory trade. A Moby Dick for elephants, The Elephant Graveyard is as rich with elephantalia as its predecessor was with whalology, and as informed by Melville’s incantatory prose and philosophical concerns as it attempts to understand why bad things happen to good people.

DANA AWARD: BEST NOVEL OF THE YEAR (2015)

Part rollicking epic, part multi-generational ghost story, part disquisition on our original sins, The Elephant Graveyard delivers a vivid, merciless portrait of America in all its glory and monstrosity. Boman Desai has built from such ambitious material a deeply human novel, large-hearted and bold, chock full of rich characters and commentary. [A] great read, a terrific novel!

Lewis Robinson (Officer Friendly and Other Stories, Water Dogs)

[A] spellbinding novel, evenly paced, that follows a circus troupe as it deals with a tragic event…. Filled with hilarity and pathos, this narrative takes readers on a rollicking ride…. Desai paints a fascinating picture of a throbbing circus in Kendall Green [Ohio] in 1948, creating characters that are multifaceted and bringing to life the circus culture. Readers get a close view of the lives of bareback riders, joeys, roustabouts, and bullmen. The story is told from the perspective of a ghost and in a tone that is both eccentric and observant…. The elephant inspires both delight and pathos as readers follow its journey in the circus. Overall, this is an original, deft, and balanced tale that … holds your attention from the jump and doesn't let go.

Christina Prescott (The Book Commentary)

When a man named Elbo de Bleu, fleeing from the police, seeks refuge with the circus, his arrival precipitates an intricate series of events that steadily spirals out of control and results in Hero [the blackest elephant in the world] being poisoned and Spike [his handler] landing in India with a guide named Prem W. Gupta. Spike narrates the tragedy at the heart of his moving story from a wiser and sadder future point: "Despise me if you will, I would think less of you if you didn't, but you couldn't despise me more than I despised myself….” [A] tale of crime, circus life, and enlightenment.

—Kirkus Reviews

The novel offers the reader a leisurely, luxuriant view of the lives of joeys, bareback riders, roustabouts—and especially bullmen, those who work with elephants. Funny and tragic, what sets Desai's work apart is the exuberance of the narrative style and the lushness of the prose, [creating] the mesmerizing sensation of a circus seen by a child for the first time.

Michael C. White (Soul Catcher)

Desai's exuberance for elephants and circuses shines through the affluence of curious trivia he infuses into the narrative. He illuminates the dark side of the sparkling mid-century circus world–the complete lack of care for human and animal lives for the sake of others profit and entertainment—and offers a new perspective on it by linking it to the intertwined bloody trades of slaves and ivory that have cost Africa, and the world, so much for the sake of filling some pockets…. The stunning and often changing background, the paranormal elements, the big cast and even bigger drama, contribute to an atmosphere of mystery and operatic scope and feeling…. Desai strongly captures the milieu, both its dusty grandeur and its horrors, as well as a deep yearning to belong that almost anyone can relate to…. Readers fascinated by the circus, elephants, and social issues will find much of interest here.

—Booklife

BACKGROUND

For the longest time, my two cultures, Indian and American, merged only in dreams. I looked continually for links between the two in my writing, but the immigration theme had long been flogged to death (third-worlders with one foot on a dirt track, the other on an escalator), not least by myself, and I wanted to find another way.

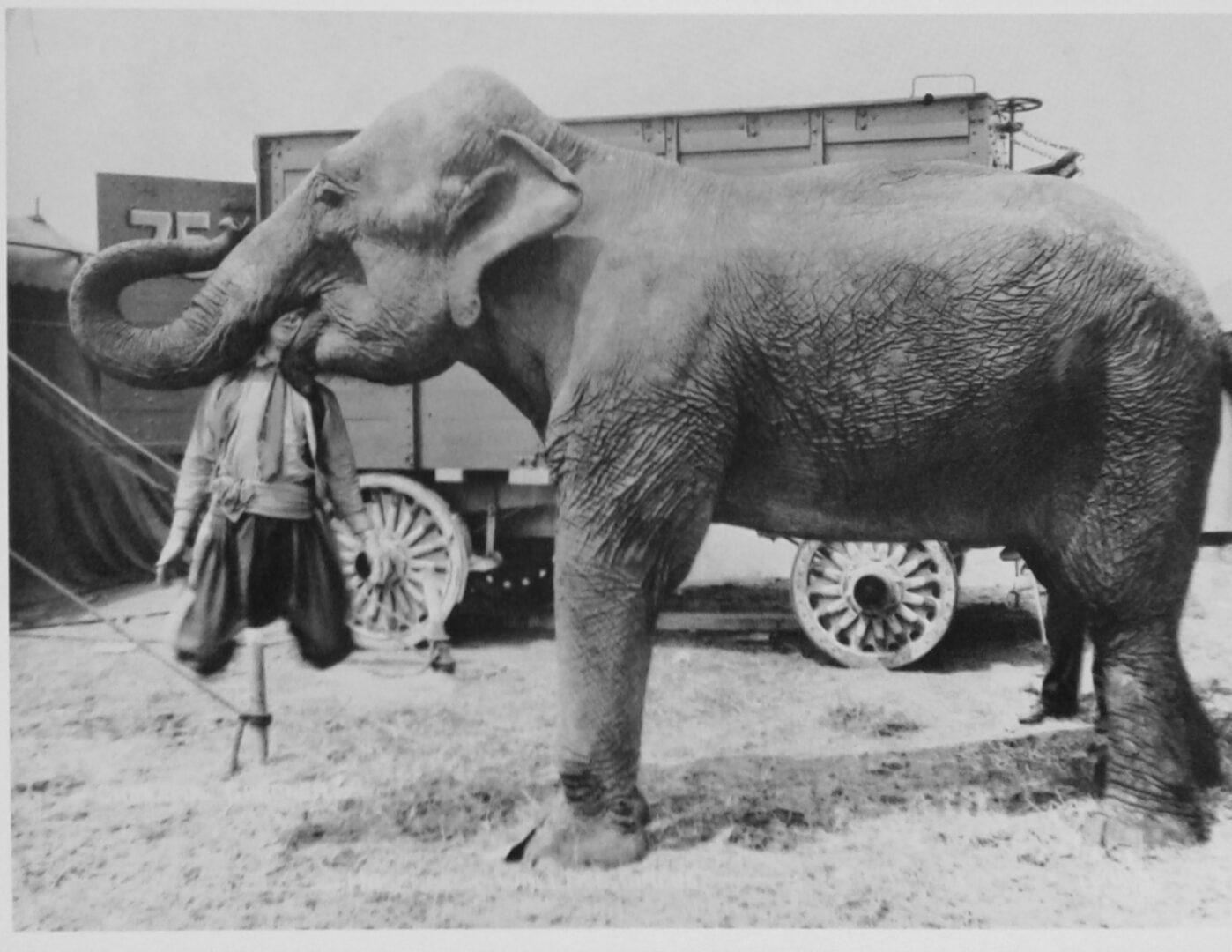

The elephant suggested itself as an option: an Indian elephant in America. It is the favorite animal of many, including myself, but only in an academic sense, a favored status that invites neither the risk nor sacrifice of a Bullman, handler, or mahout. As a boy, I'd had elephant cufflinks, elephant bookends, elephant lamps, and elephant patterns on curtains and bedcovers, among other such elephantalia. I'd asked for a two-foot-tall wooden elephant for my Navjote (the equivalent of a Bar Mitzvah or Confirmation). The mother of a friend once called my mother to say that I'd spent the entire afternoon of a visit drawing pictures of elephants. My first published novel was called The Memory of Elephants. Still, that title was a metaphor for long-term memory, nothing to do with the great grey beast itself—with which I'd had little contact except at the Bombay zoo where I'd ridden the mighty animal on one of two benches (strapped back to back on its back), and of course at the circus though only from a distance.

To begin, I had little in mind except to have an elephant feature in the novel, following which I read as much as I could on the animal, researching for facts as much as ideas. I had planned to place it in a zoo, but the circus soon suggested itself as a more colorful alternative, following which I researched the history of the circus.

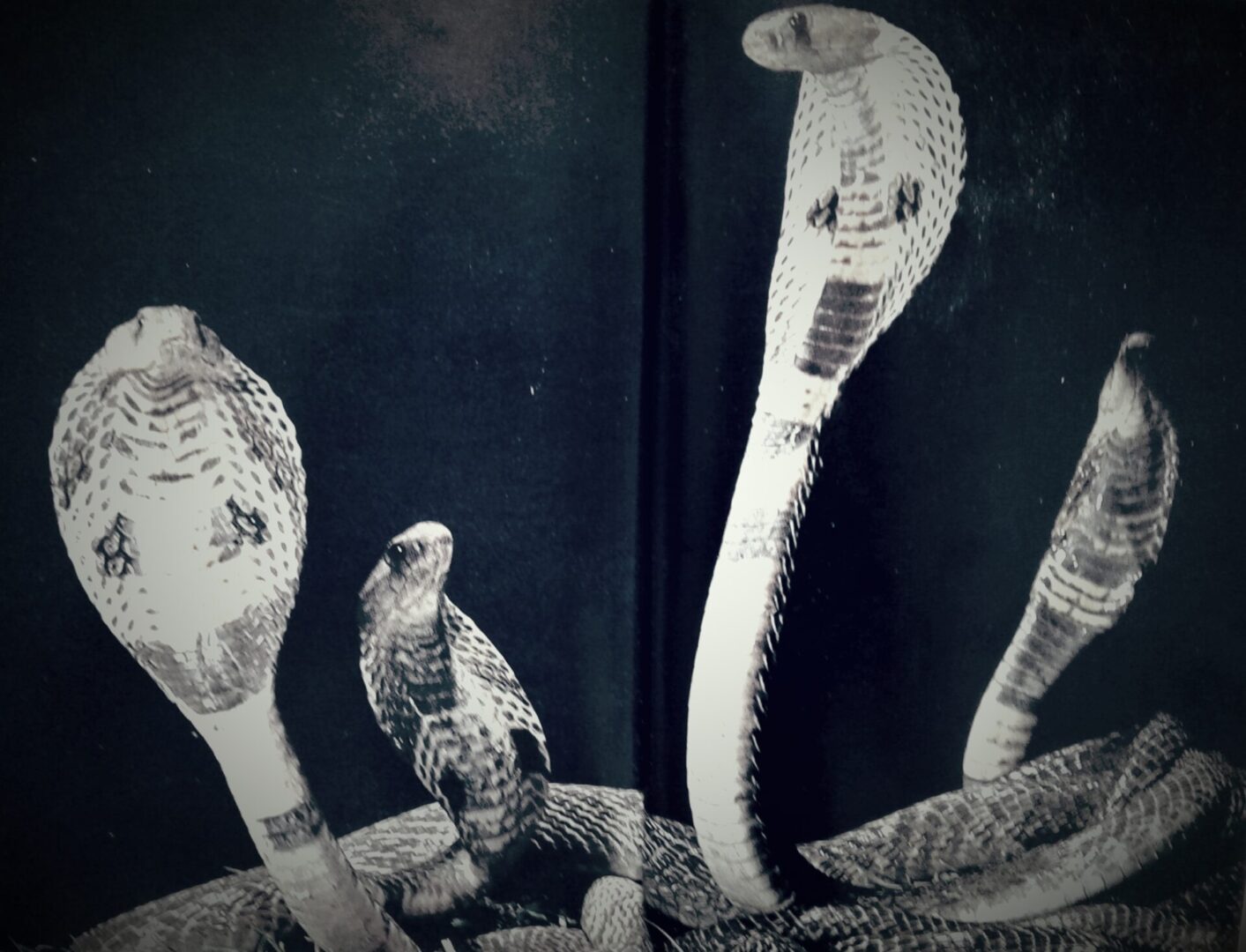

A photograph in National Geographic of a man being lifted by his head in the mouth of an elephant gave me the central plot. The plot was further developed by another indelible image in National Geographic of a king cobra standing six feet tall in a graveyard: malevolent, magisterial, and magnificent. It is the only snake that can stand upright, a third of its length (almost 26 feet at its fullest). A full-grown king cobra could look down on John Wayne.

Moby Dick suggested itself almost immediately as a model for obvious reasons, as much for the mammal as the metaphysics. Rereading the book twice, I was moved to fillet my novel with some of Melville's incantatory prose, to rise to a more luscious prose of my own (You can count on a ghost for a fancy prose style, a sentiment I filched from Nabokov), and to revisit his themes of death and obsession.

EXCERPTS

One

As juggler and tumbler I might have been counted among acrobats, but as a bullman not even among joeys. I was barely above ponypunks and dogboys in the circus dungeon, while Eileen hovered among clouds drifting past turrets and towers. Each of us did flips and tumbles, but mine were on the broad back of Hero, the blackest elephant in the world, and hers on the thundering rump of her Andalusian, Andromache, the difference between performing in the middle of a plain and the middle of an earthquake—and differences there were more and plenty. For starters, she was a celebrity, flashed on the posters, tycoons gave her diamonds, beer barons gave parties in her honor. I couldn't compete.

As luck would have it I didn't have to compete. She knew better what to do with coals smoldering in the basement than I did. She invited me into her trailer one lazy Sunday afternoon in Wilmington, Delaware (we played different towns every day of the week, resting on Sundays). I lacked grace, I lacked gravity, I lacked authority; I lacked emeralds and other glittering flowers; I lacked the means to make them available; but though my face was as smooth as a girl's my appetite was more rapacious than that of the most heavily bearded man, my stamina that of a stallion. I marveled at my fortune, the girth of her thighs, each thick as a hydrant. I appeared and disappeared at her pleasure, asked no questions, and said little, not because I had little to say but because I didn't want to reveal how little I knew about the world, how littlesuited we might be for each other.

Two

Elbo didn't move, but could see from where he lay on his back that he was at one end of a long room with cages on each side mounted three feet above the floor. A doorway stood at the far end of the room and he prayed to reach it safely, prayed the cages were locked, but couldn't find the courage even to move. He felt safe only as long as he didn't attract attention. Even behind bars, the tiger on high, chin tufted in a Vandyke, one gleaming fang overhanging a furry lip like that of a crocodile, appeared as regal and menacing as a sphinx, as if he could reach Elbo anytime he chose by extending one dangling paw. Elbo could have lain there until someone found him, but he was no more enthralled about the prospect of another term in jail at the end of his adventure, and plucked courage finally to slide on his back, imperceptibly as possible, toward the door.

The first move, the most difficult, attracted the most attention. Something touched his knee and he kicked reflexively sending it clattering as loudly as a motorbike through a mausoleum, the object he had picked and tossed through the window, a blowtorch. The tiger erupted with another jackhammer roar, three inch claws raking the air inches from his face, other cats nudging the bars of their cages, grunting and growling and puttering like tractors. Elbo would have been no more terrified had the Great Sphinx itself cracked out of its stone death to roam the plains of Ghiza. Had he not been on his back he might have fainted again, but when the tiger failed to touch him he slid again toward the door, moving in infinitesimal increments, as if he were running a gauntlet between the cages, as if he were on a tightrope though there was plenty of space between the cages along the center of the room.

Three

The elephant was more grey than white with salmon highlights, but its hair was white contributing, more than its pigmentation, to the illusion of whiteness even by night. Three-foot tusks, curved like scimitars, gleamed like pearls. The eyes were midnight blue, not the common pink of albinos. Long lashes fluttered, feminine and flirtatious.

The ammoniac smell of piss was predictable, but another smell of rot and sewage grew stronger: musth. The elephant was rutting for females in estrus, black liquid seeped from gashes in its temples appearing like makeup running in rain. The abundance of testosterone made it an impossible animal for the most experienced of mahouts, but facing the elephant was no mahout with the metal claw of an ankus, but a man with a rifle—Quint in khakis and cargo shorts—and off to the side, where the tall timbered wall of the boma met the ground, fallen on her flank, frozen with fear and shock, also in khakis and cargos, sola topi face up beside her, lay Mercedes.