J. R. Salamanca / Lilith

I was 17, living in Bombay where I was born and raised, when I first read Lilith, the story of a schizophrenic woman whose therapist fell in love with her. I had wanted to be a writer since I was 11, but a crisis of confidence had me wondering what I might add to the works of Shakespeare and Tolstoy among so many others. I regained confidence reading Lilith, a book of which I had been ignorant, but which shook me so mightily that I wondered if I might similarly shake other anonymous readers with an anonymous book, but I was shaken in large part because I disagreed with the conclusion of the novel. Lilith may have been mad, but she was also highly intelligent and intensely creative. Among other things, she had constructed a flute which played quartertones, allowing her to play melodies otherwise unhearable—and a palette of ephemeral pigments from herbs and flowers, allowing her to paint pictures otherwise unseeable. She was also lovely and I fell in love with her, rooting for her and Vincent (the therapist) to make a success of their love against the rationale of the universe. When the romance collapsed, I was shattered.

Five years later, after I had moved from Bombay to Chicago, I found a copy of Lilith in a Woolworth’s. Forewarned, I wasn’t as shaken by my second reading, appreciating the book for its story and lyricism but still infatuated with the character. I read it a third time after receiving my undergraduate in psychology, shaken for a different reason. I could see now how carefully Salamanca had infused the narrative with the symptoms of Lilith’s madness, symptoms that had escaped me during the first readings, but were now cause for anxiety: so strong was her gravitational pull I didn’t think I could have resisted such a woman in real life! Another couple of readings and I felt confident I was no longer in her thrall, but the last time I read the book I found an insight I had missed during the first 5 readings. I had needed to get over my infatuation to discover the final revelation.

Vincent’s father had left his mother for another woman, covering the family in a caul of shame, the unforgiving small town too self-righteous for its own good. With the advent of the 2nd War, wishing to regain standing, Vincent’s grandfather urged him to be the first to enlist, promising a college education in return. Vincent could think only that his grandfather didn’t care whether he lived or died—and, returning from the War, refused not only the education, but also the job his grandfather offered in his dry goods store, knowing how much his refusal would hurt his grandfather, finding himself instead the job at the asylum. It’s not until Lilith is lost forever, not until his grandmother dies, that Vincent and his widower grandfather grow closer, each recognizing how selfishly they have hurt each other.

Just 17 when I first read the book, I not only recognized my own growth through subsequent readings, but also a parallel circumstance in my own life, how I had selfishly hurt someone I loved deeply because I had been hurt similarly by the same someone—just one more example of how the best fiction provides insights unavailable to people who like to read about only “real” things.

I wrote to Salamanca, then a professor at the University of Maryland, to let him know how deeply his work had affected me and was thrilled to hear back from him. Among other things, he wrote, “Here is a peculiar thing for which I cannot account: the most appreciative, thoughtful, and intelligent letters I have ever received about my books have all been from Indian people. There must be a reason for this, and it’s one which I’m sure will eventually lead me to your native country, on whose soil, alas!, I have not yet trod.”

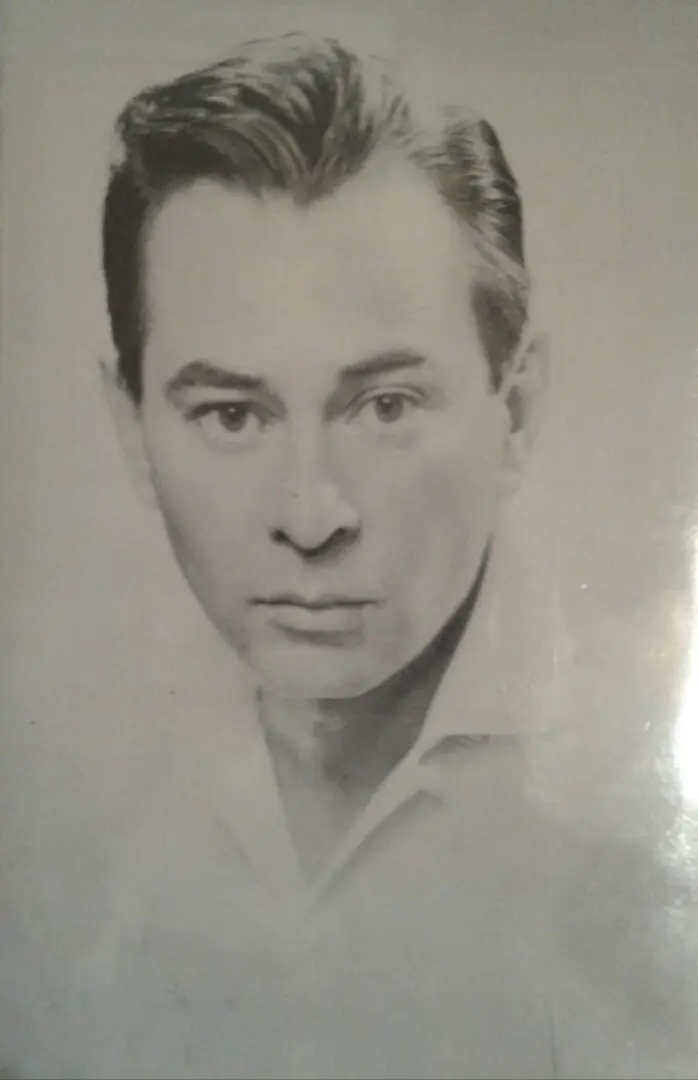

We had a brief correspondence before I was able to send him a copy of my own first novel, The Memory of Elephants. The letter pictured below is his kind response to my book. (To clarify the last couple of sentences, the book was published in the US by the University of Chicago Press 12 years after its publication in the UK.) The Lilith book cover above is of the copy I found at Woolworth’s (more salacious than the cover I had in Bombay). The portrait of young Salamanca is from the jacket of his first novel, The Lost Country, through which I discovered him. The book was made into an Elvis Presley movie, Wild in the Country, one of his early dramatic roles, just 3 songs and a supporting cast including Millie Perkins, Tuesday Weld, and Hope Lange!