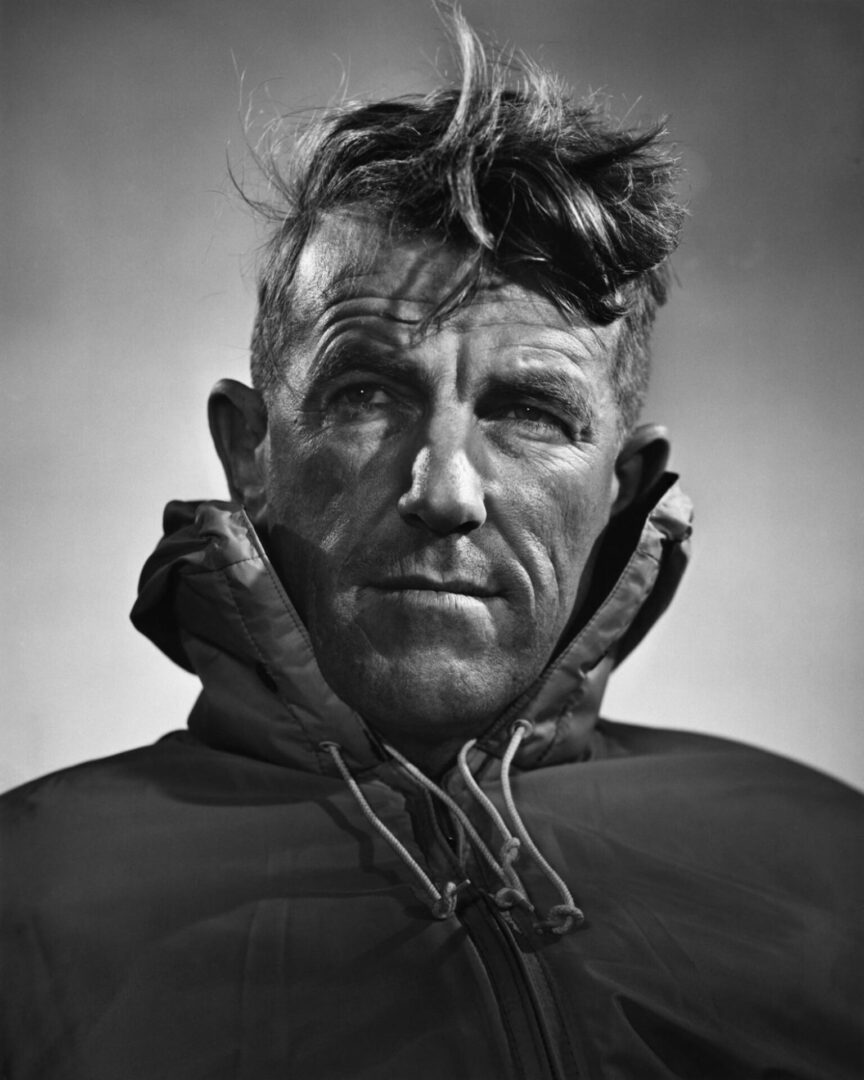

Sir Edmund

I had a part-time job conducting telephone surveys in the Sears Tower when I graduated in 1976 with a degree in Psychology. The office manager said the market analysts knew my work and I had the inner track to a career in market analysis if I wished. I said thanks, but no thanks, I had a novel to write and needed to remain part-time. I took a couple of years to write a short novel, but 5 rejections snuffed my enthusiasm and I returned to the office manager and asked what I needed to do to become a market analyst. She gave me a book, Dress for Success, by John T. Molloy. I was in the right place, I just needed to wait for an opening, but in the meantime I had to look the part, a matter of wearing blue suits, subdued ties, et cetera. (I was then wearing sandals and a braided leather headband to work.) I chucked the sandals and headband, bought some cheap suits and ties, and settled into a trainee position while waiting for an opening.

As it turned out, Sears had commissioned Sir Edmund Hillary to head an expedition of 4 boats they were marketing from the mouth of the River Ganges in the Bay of Bengal to its source in the Himalayas. A documentary of the expedition, From the Ocean to the Sky, was broadcast on PBS. Sir Edmund was my first hero (my family had holidayed in Darjeeling in 1954, the year after he and Tenzing Norgay had ascended Everest) and I was happy as a kitten with a ball of twine on July 3, 1979 (I keep a diary) as I scampered around the desk of this great-hearted giant from New Zealand to shake his hand.

We saw a preview of the documentary in the Tower the same day and returning to my floor I found myself alone with one of the senior analysts in the elevator. He looked thoughtful and I asked if he had something on his mind. He confessed the documentary had made him reflective. Here was Sir Edmund, ten years older, for whom everyday was an adventure, but for him every day was like the day before. I asked if he’d wanted to climb mountains, but he shook his head. He wasn’t adventurous, but he wished sometimes he’d written a good book. I said he could still do that, but he shook his head again. You got married, you had children, you had responsibilities, there was no time. I said maybe after he retired and he laughed: of course, everyone wrote a book after they retired.

Six months later, still in his mid-50s, he died of a massive heart attack. My first thought was that he would never write his book, my second that I would never write mine if I stayed where I was. I returned to the office manager to say I had a book to write and wanted to go back to part-time work. She could not have been lovelier cautioning me: (1) I would be demoted (meaning less pay); (2) I would be a part-timer (still less pay); (3) I would lose benefits. I was 29, I had second thoughts, but realized the longer I dawdled the more difficult it would get. I published my first novel in 1988, not without the attendant difficulties, not before I had long lost count of my rejections, not without an episode that deposited me via an ambulance in a hospital bed. William Styron once said writing a novel was like pushing a pea uphill with your nose. I don’t know about that. D. H. Lawrence’s sister-in-law once said writing a novel would break your heart and if it didn’t break your heart it wasn’t any good. I don’t know about that either. But it would be fair to say writing a novel is akin to climbing a mountain of a different gradient, living in a state of siege, the province of solitaries, losers in love, prisoners of war, the Irish of Northern Ireland, and other such long-distance runners.