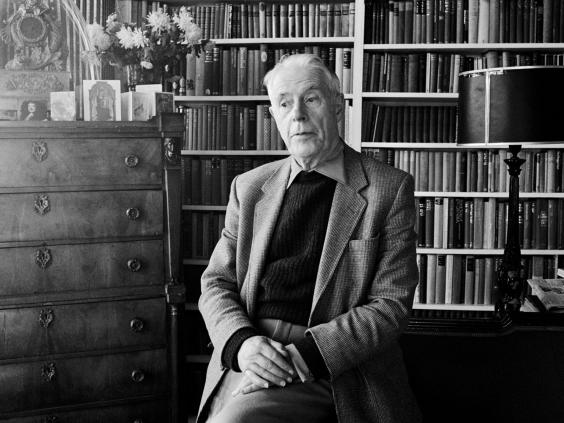

Powell, Anthony: A Dance to the Music of Time

I started reading A Dance to the Music of Time with high expectations brought about by its reputation as much as its sheer size (1,000,000+ words, 3,000+ pages). The author, Anthony Powell, is justifiably called the English Proust for his ambition, even tipping his hat to the French Master when his narrator (Nick Jenkins) reads Remembrance of Things Past during the years of WWII, but his technique is as accessible as Proust’s is not, his sentences as moderate in length as Proust’s are not, and where Proust sometimes goes down like spinach Powell goes down like candy.

The series comprises 12 novels, or 4 quartets (sometimes called Spring, Summer, Autumn, and Winter, sometimes the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th movements of a symphony). The parallels are specious: the books correspond neither to the seasons nor the format of a symphony. The story follows the lives of 4 friends from high-school days to heydays (and low days), Britain of the early 20th Century highlighting the backdrop. The cast of characters is bountiful and diverse (financiers, politicians, artists, models, privates, generals, writers, critics, musicians, academics, psychics, servants, and industrialists among many others), none of them particularly memorable, but for better or worse the series is descriptive more than prescriptive, concerned with breadth more than depth, knowledge more than insight.

I read the novel 2½ times, more fully to encompass its design, but instead of growing on me with greater familiarity (as do Tolstoy and Hugo and Wharton and Austen with subsequent readings), instead of blossoming under a brighter light, the story seemed to withdraw, afraid to be burned by too close a focus. Despite its accessibility, the world of this Dance remained under wraps. The author appeared to do little more than move large swathes of people around the country in a perfectly Olympian exercise of authorial control, killing some, birthing others, coupling others, decoupling still others, all apparently at whim with no regard to motivation or credibility, mostly just to get on with the story.

I came to the book to praise the Dance, not only putting in a great deal of time to read and reread the books, but making notes, chronological charts, et cetera, the only way to grab so vast an enterprise by the scruff, but once I found myself behind the impressive façade, its flaws fell obediently into place: (1) Multiple coincidental meetings reduce London to the size of a hamlet. (2) A single narrator’s monochromatic perspective forces many pivotal scenes to be summarized. (3) A stiff upper lip microwaves even the grandest situations to the driest prose. (4) New characters continually crisscrossing the narrative require continual reboots of the reader’s faculties. (5) The mise en scene, even when trailing characters from party to party, remains bleak as a London fog. (6) Winter (or the 4th Movement) appears to jump the rails entirely, the story narrowing to the humiliation of the book’s most unregenerate character, as if the author did not know how to end his opus and opted for a grand guignol conclusion out of keeping with the rest of the manuscript. Perhaps the fairest assessment might just be that Powell’s intention was to illuminate a wide panorama of characters with no intention of studying any of them in depth—which would place him several notches below such giants as Hugo and Tolstoy, but perhaps that’s not too shabby a place to be.