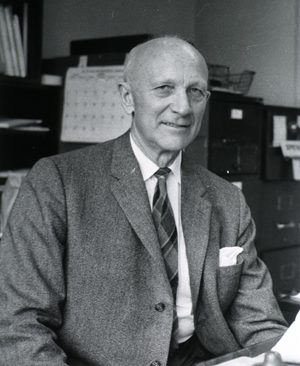

Dr. Wilder Graves Penfield

A youthful indiscretion gave me the key to my first novel. The details do not matter (boy meets girl, boy loses girl), but the end of the affair was as decisive as the drop of a guillotine. My head remained on my shoulders, but I was suddenly groundless, rootless, a wraith of a man, a storm unto myself, a tempest in a teacup to the world. Nothing existed outside my cave of gloom until I learned in a psychology course about Dr. Wilder Graves Penfield, a Canadian neurosurgeon (also a football coach at Princeton, veteran of the Great War, novelist, and autobiographer), who discovered the ridge of tissue in the brain corresponding to epilepsy. Peeling back the scalps of his patients, probing their naked brains with electrodes, he was able to locate the problematic areas and cure 75% of his patients by surgically removing the ridge.

More importantly (for my purpose), he established a link with memory which he postulated was stored in the temporal lobes. During one probe, a middle-aged housewife from New Jersey said she felt she was giving birth to her first child all over again, vividly recalling sights, sounds, and smells of the delivery room. On another occasion, a patient found herself in the living-room of the house in which she had grown up, the march from Aida on the phonograph, the music stopping when the probe was removed, restarting when it was reapplied. The penny dropped: my faithless friend wasn’t lost as I had imagined, but lodged irrevocably in my brain—irrevocably, but not retrievably.

I solved the problem by creating a character, Homi Seervai, a whizkid from Bombay, who invents a machine, the memoscan, which allows him to scan his brain using noninvasive laser surgery, to locate the memory of time spent with his inamorata. Under the influence of the memoscan, he becomes oblivious to everything else. Setting the memoscan to function in a loop, repeating the memory of the haloed hours, he knows he will die of dehydration—but whether it’s a matter of dying or living forever with his love is a matter of perspective, even a matter of indifference for Homi as he hooks himself to the memoscan.

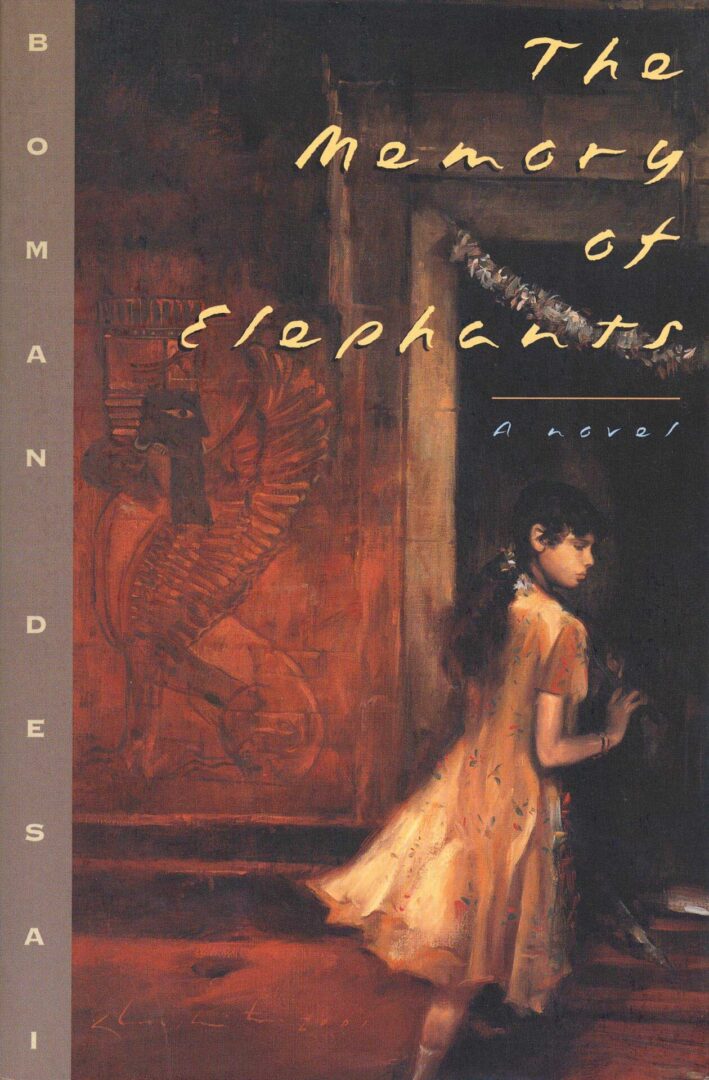

Something goes wrong. Instead of sticking to the assigned groove (the memory of the affair), the memoscan delves into his Collective Unconscious (the memory of mankind), and Homi is hailed by multitudinous voices from his past, relatives dead and alive, ancestors centuries-dead, providing me with the frame for a generational saga of a Parsi/Zoroastrian family, accounting for the title: The Memory of Elephants. A favorite review on Goodreads read: “I love magical realism and time travel and family history stories and Indian culture in all its forms. This book has all of that. I could easily see this novel turned into a film.” Me, too. Strangely, I’m not a fan of genre fiction, least of all magical realism (as if Realism, despite the evidence of galaxies spanning light years across the universe, is not magical enough)—but I’m happy enough to embrace all genres incidental to the straight line of my inspiration.