Clara’s 16th

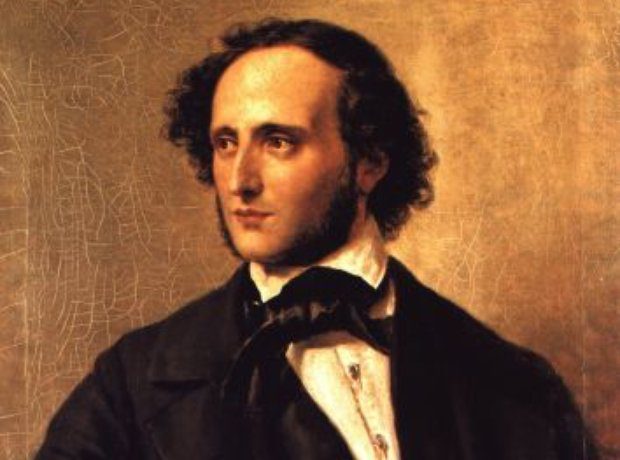

After dinner on Clara Schumann’s 16th birthday [September 13, 1835], Felix Mendelssohn assembled the guests around the piano and put on his gloves. By special request he was to provide the company with an impersonation of Franz Liszt whom none of them had seen. Mendelssohn smiled. “Keep in mind, Liszt has straight long hair reaching his shoulders. When he shakes his head it blows like a veil in the wind. My hair, as you can see” (he stuck his chin in the air, shaking his head) “is too stiff. It does not move at all.”

The company laughed, everyone attentive.

Mendelssohn straightened his back and swept the room with a rude stare, silencing the laughter. He pulled his gloves by their tips with firm, short, measured tugs, tossing them with a languid flick of his wrist to the floor. Clara no longer knew whether to laugh, nor did the others. Mendelssohn appeared vain but grand, arrogant but confident, mesmerizing but vexing. The impersonation was so profound that when he bowed his head over the keys Clara could imagine Liszt’s long hair falling like a veil, covering his eyes and face—and when he shook his head the veil was brushed aside.

He flung his head in the air, eyes fixed like hooks on Clara, raising his left hand above his head, swooping onto the lower regions of the piano in a sudden, loud tremolo. His right hand swooped to join his left, both hands taking scales at incredible speed, now ascending, now descending, swooping out, swooping in, his eyes never once releasing Clara, his fingers appearing to have minds of their own. He swayed in large amplitudes to the music, as mobile as Clara had become still, never doubting he could have swiveled his head entirely around without losing a note, hands like eagles, eyes like wolves, so lost in her admiration that she forgot to breathe. No one had stared at her as he did and she giggled to cover her discomfort—at which point Mendelssohn smiled, himself again, and she knew he wished her comfort again.

Clara was ready to applaud as the concluding cadences fell, but Mendelssohn slid not only into another work, but into another persona. Whereas his audience had earlier been his primary focus, he now seemed oblivious to their presence, his hands hovered where earlier they had soared, caressed where earlier they had struck, skipped across octaves where earlier they had leapfrogged. Even the music changed, you heard emotion and delicacy where earlier you had heard speed and power. Clara whispered, unknown to herself, “Chopin!” recalling the only time she had heard him, recognizing the sound she had not understood before, evoked with the pedal, blending notes where others, herself included, could only blur them—and Mendelssohn had evoked the specter perfectly. In Mendelssohn she had received for her birthday 3 pianists in one.