Beethoven

When conducting, Beethoven rose on his toes to mark a fortissimo, sweeping his arms wide—and fell to a crouch to mark a pianissimo. Once, conducting a concerto from the keyboard, he swept his arms knocking off the candles lighting his music stand. Two choirboys were sent to stand at the sides of the piano holding the candles, the orchestra started again, Beethoven made the same gesture, smacking one of the boys in the face while the other ducked, so infuriating the composer that when he started again he broke several strings on the first chord.

Jan Swafford’s biography provides other similarly comic episodes, but for the most part Beethoven’s was an immensely tragic life, almost as if he paid for all his glory in suffering. His mother had said—“Without suffering there is no struggle, without struggle no victory, without victory no crown”—but Beethoven’s countless crowns might all have been thorned.

His mother died when he was 16, his father sold her clothes, and the young Beethoven was often privy to the spectacle of neighbors parading in his mother’s clothes. His father turned alcoholic, loved his son with an iron fist and an explosive temper, something Beethoven carried into the world himself as he became responsible for the household (two younger brothers and his father) at the age of 20.

Everyone knows he wrote his best work turning deaf, but few know his teenage years saw the onset of stomach seizures that lasted a lifetime and he suffered from chronic diarrhea, owing supposedly to lead ingested from spa waters, cooking utensils, or adulterated wine which corroded his digestive tract and aggravated his liver.

One summer, a commissioner of police was interrupted at dinner by a constable saying a tramp they had jailed for vagrancy howled continually that he was Beethoven. The commissioner dismissed the constable saying he would deal with the tramp in the morning, but was awakened in the middle of the night by the constable saying the tramp demanded the local music director be called to identify him. Herr Herzog was called, identified Beethoven positively, took him back to his own house, and gave him his best room.

It wasn’t the only time he was jailed for vagrancy. Another time the mayor of Baden was called on a similar errand and provided a state coach to take Beethoven back to Baden in style. The police were not to blame, Beethoven was as careless of his appearance as of his quarters. One visitor to his home reported a steaming chamber-pot lodged under his piano.

There were other bedevilments: composers sold their works for a flat fee; there were no royalties; there were no copyrights; neither plagiarism nor piracy was illegal; musicians were their own agents; they made money from performances and patrons, the first of which were forbidden Beethoven as his hearing deteriorated, the second of which became fewer with Napoleon’s armies storming the gates, bombarding the city. Accolades run from clever to talented to gifted to genius, there is no doubt where Beethoven fit, but in addition he had grit, determination, self-confidence, and inspiration more bejeweled than the kingliest crown. When inspired, oftentimes during walks through the countryside or a spring rain (he found inspiration in water), he entered what his friends called his Raptus, a state of fugue during which he was not only deaf, but unseeing, unfeeling, apparently in a different world.

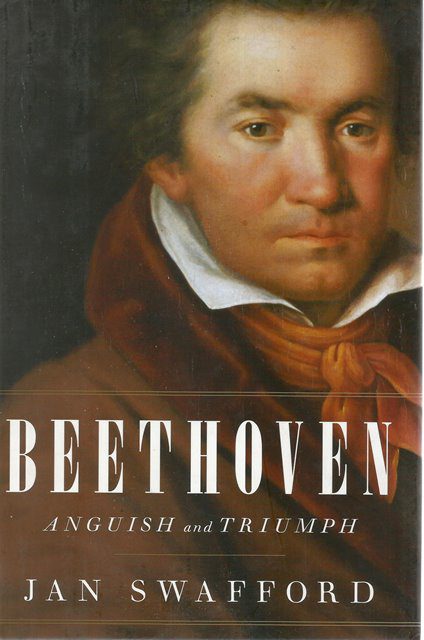

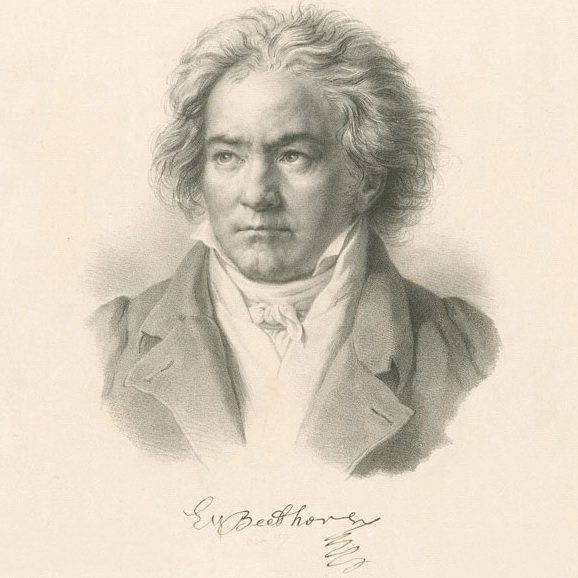

Regarding women, his reach was unequal to his grasp. He was more republican than democratic, frequenting prostitutes while falling for aristocrats, but noblewomen marrying commoners lost their privileges, their children could not inherit their titles, and asking a countess to give up so very much for a freelance composer of uncertain income was asking too much. Not even genius could surmount those odds. Besides, by most accounts, despite romanticized portraits (compare the two above), he was homely—and his father’s hot-temper did not help.

In the end, among other things (including jaundice), he swelled with edema, a specialist was called to drain him, his abdomen was cut (no anesthesia in those days), 25 pounds of water spurted, he was cut 3 more times in the next 2 months, water from his belly soaked the bed and gushed across the floor. He joked with his doctor: “Professor, you remind me of Moses striking the rock with his staff.”

At the very end, so the story goes, a thunderstorm darkened the window, Beethoven jerked awake to shake his fist at the sky, the same fist that had written the Moonlight Sonata, the Waldstein, Tempest, Eroica, Kreutzer, Archduke, Emperor, Egmont, and Ninth among so many more, each creating tsunamis in the world of music. He not only created more works that alone might have made the reputations of lesser composers but changed the course of music from a stream to a river in flood.

The inscription on his gravestone reads: BEETHOVEN. No more is needed. He lies in better company dead than he did alive, joined the next year by Schubert and a few decades later by Brahms. The trio lie side by side in the giant Zentralfriedhof, Vienna’s main burial ground, their contribution to the world, singly or jointly, incalculable, Beethoven the font.