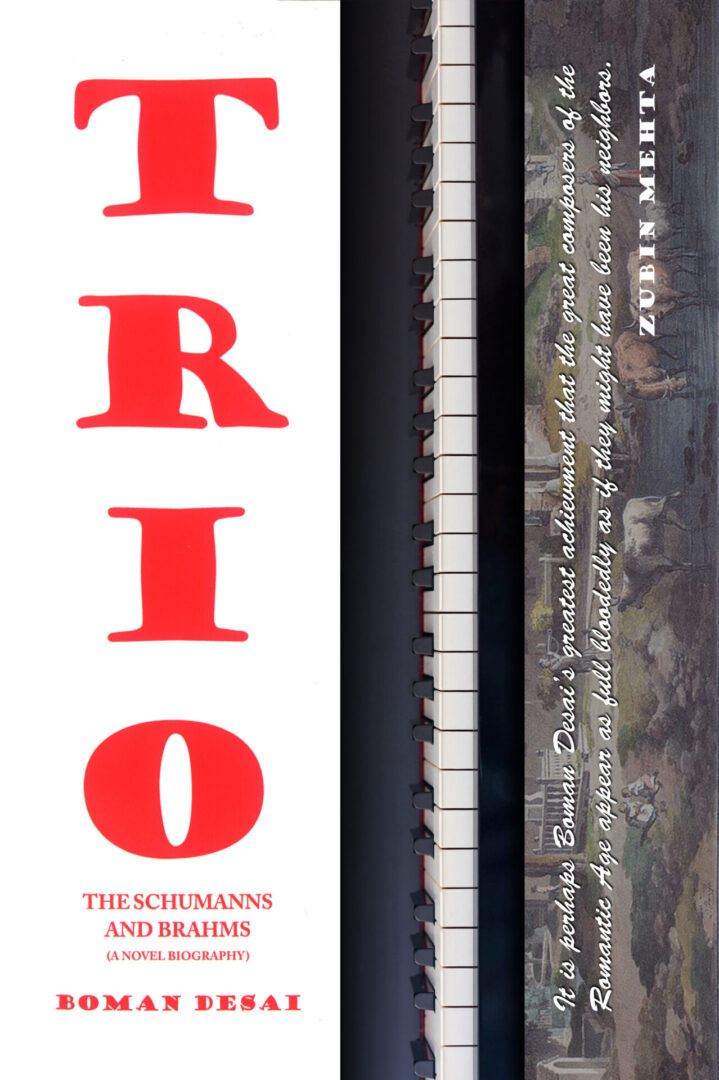

TRIO

A Novel Biography of the Schumanns and Brahms

The trio comprises three musical geniuses: Robert and Clara Schumann and Johannes Brahms. Clara married Robert with whom she fell in love when she was just sixteen, though it meant challenging the iron will of her father who wished her to marry an earl or count, certainly not an impoverished composer. The Schumanns had eight children and Robert’s greatness as a composer was never in doubt, but he was also mentally ill, attempted suicide, and finally incarcerated himself in an asylum where he died two and a half years later.

Johannes Brahms entered the picture shortly before the incarceration and fell deeply in love with Clara, but was just as deeply indebted to Robert for getting his first six opuses published within weeks of their meeting. Clara was forbidden to see Robert in the asylum because the doctors feared she would excite him too much. Brahms became a go-between for the couple, ferrying messages to and fro, but both loved Robert too well to abuse his trust. Brahms learned instead to associate deep love with deep renunciation—and, coupling this love with early experiences of playing dance music for sailors and prostitutes in Hamburg’s dockside bars, he became a victim to the Freudian conundrum: Where he loves he feels no passion, and where he feels passion he cannot love.

Germany grows in the hinterland of the story from 400+ principalities to one nation under Bismarck. The great composers of the century (Mendelssohn, Chopin, Liszt, and Wagner among others) have their entrances and exits—and the ghosts of Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert are never distant.

Though firmly grounded in fact, the book unfolds like a novel, a narrative of love, insanity, suicide, revolution, politics, war—and, of course, music.

A Kirkus Reviews BEST BOOK OF 2016!

A riveting dramatization of musical history…. Desai has produced a magisterial work, which is clearly the result of astonishingly thorough research. Although the story revolves tightly around the three main figures, there are also fascinating cameos by such musical luminaries as Richard Wagner, Franz Liszt, and Fréderic Chopin, and he memorably depicts the ego-driven rivalries between them. Each has a unique personality, and the author does a lovely job of dramatizing their quirks.

—Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

Boman Desai writes so compellingly that it is like discovering this most romantic of stories anew. The great composers of the age make appearances when their lives intersect those of the trio, and it is perhaps Desai's greatest achievement that they appear as fullbloodedly as if they might have been his neighbors.

Zubin Mehta (Music Director: Los Angeles, Israel, and New York Philharmonic Orchestras)

I finished reading your novel, TRIO, and found it compelling and illuminating. Would that the American reading public could appreciate such a story as well told. It’s a story that Tolstoy might have told in similar terms. I do hope that it eventually gets the recognition it deserves. It is surely a tour de force.

Vernon A. Howard (Former Co-Director, Philosophy of Education Research Centre, Harvard University)

I loved and admired this book.

Diana Athill (Instead of a Letter, Stet)

I was loath to put the novel down. Exhaustively researched, charming and readable, it is a massive achievement. I recommend TRIO wholeheartedly, not only to music lovers, but to all who love to read.

Bapsi Sidhwa (The Crow Eaters, Cracking India, Water)

Conservatory Pianist on Amazon

5.0 out of 5 stars:

As Elegant and Masterful as the music itself...

Reviewed in the United States on October 26, 2012

Boman Desai's TRIO was more than a pleasant, informative read for a music lover, student, or professional musician- it is a REVELATION and really a stunning, virtuosic achievement. No other book- be it a biography or what not brings you inside the minds of Robert Schumann, Clara Schumann, and Johannes Brahms—no one would have ever even thought it possible to do. This book that reads like a novel but is full of historically accurate information, you learn so much that you feel you know these people, they become your personal friends and you can experience the world from inside their minds. The research that went into composing this book is something extraordinary... I really hope it does gets the attention it deserves from the musical world, this is an accomplishment of unimaginable depth. I can only humbly pass thank MR Desai for this gift to me and all the music lovers of the world. Please read both books, the complete work is some 800 pages of sturm und drang, appassionata, dolcissimo, and grazioso writing.

I loved your book. You completely transported me. I read it through at a gallop. The love & feeling you have for the subject comes through—you disappeared & they appeared on the page, in the flesh, & I could hear their music. Congratulations!

Sooni Taraporevala (Salaam Bombay, Mississippi Masala, Parsis, Yeh Bombay)

The language of TRIO is so vivid it makes one want to explore the composers’ repertoires which get some evocative descriptions. So do the performers them-selves: Clara’s meticulousness, Liszt’s power and bravura, Brahms’s perfection at the piano as a cocky young virtuoso and sloppiness as an old man, Mendelssohn’s spot-on imitations of Liszt and Chopin. Like the music, the book is meant first and foremost to be enjoyed—and on this account, it does not fail.

Chris Spec (Quarter Notes)

Paul Ricchi on Amazon

5.0 out of 5 stars:

A masterpiece of history in the form of a novel-biography!!

Reviewed in the United States on January 17, 2020

Verified Purchase

This substantial “novel biography” ( the author’s term) is a masterpiece of its genre. It was born of wide and deep research, it has great narrative flow, vivid dialogue and a detailed sense of time and place. It benefits from an epistolary thread that binds the chapters. It proves that, in the right hands, historic fiction need not be any less valid than academic speculation - simply not as pretentious.

Desai writes that he targeted a “general reading public, not musicologists, not academics.” This is true, but it does require—and greatly rewards—an adult level attention span. There will be those who say, “I just couldn’t get into it.” That’s fine, as long as they are aware that it is self-criticism.

BRAHMS'S WOMEN

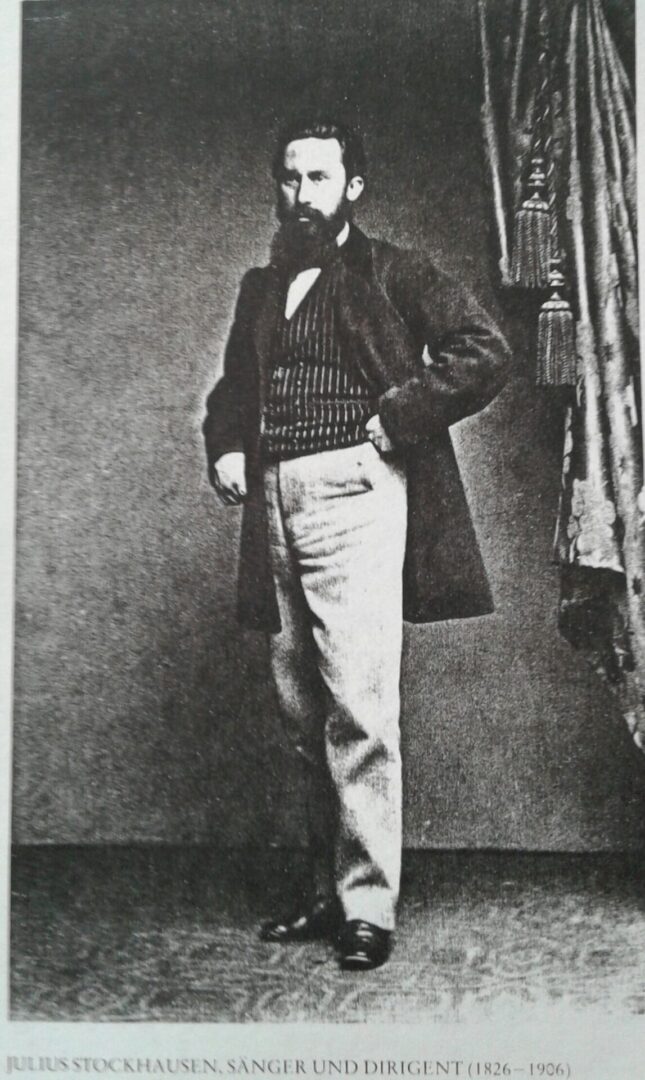

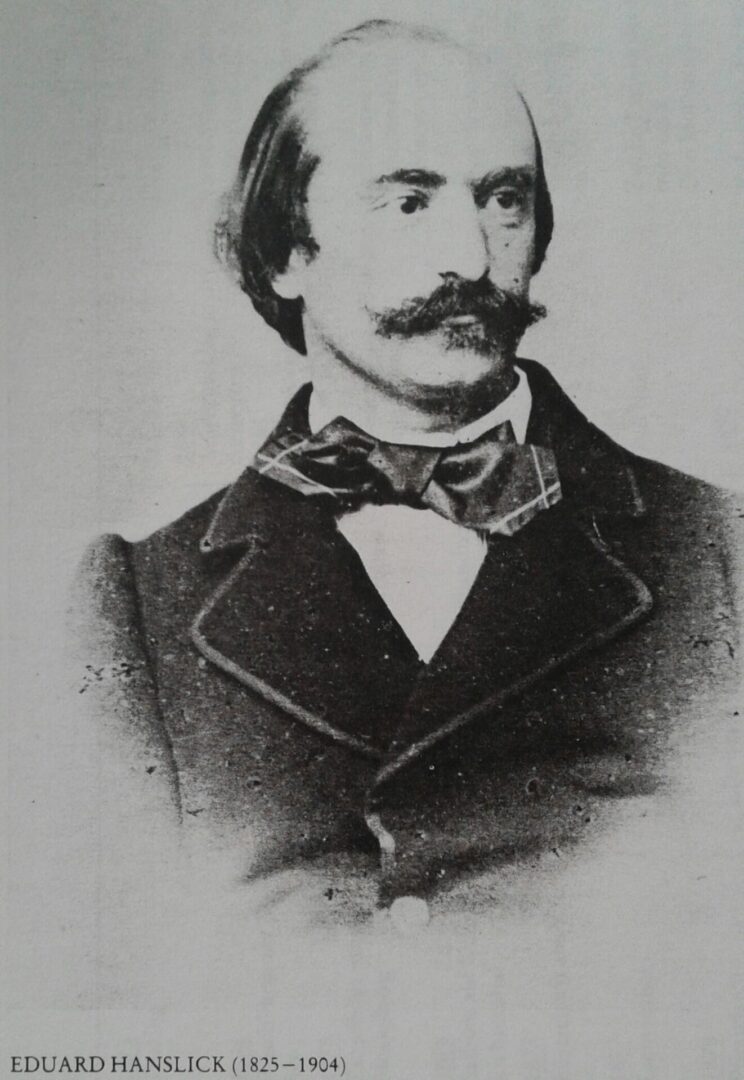

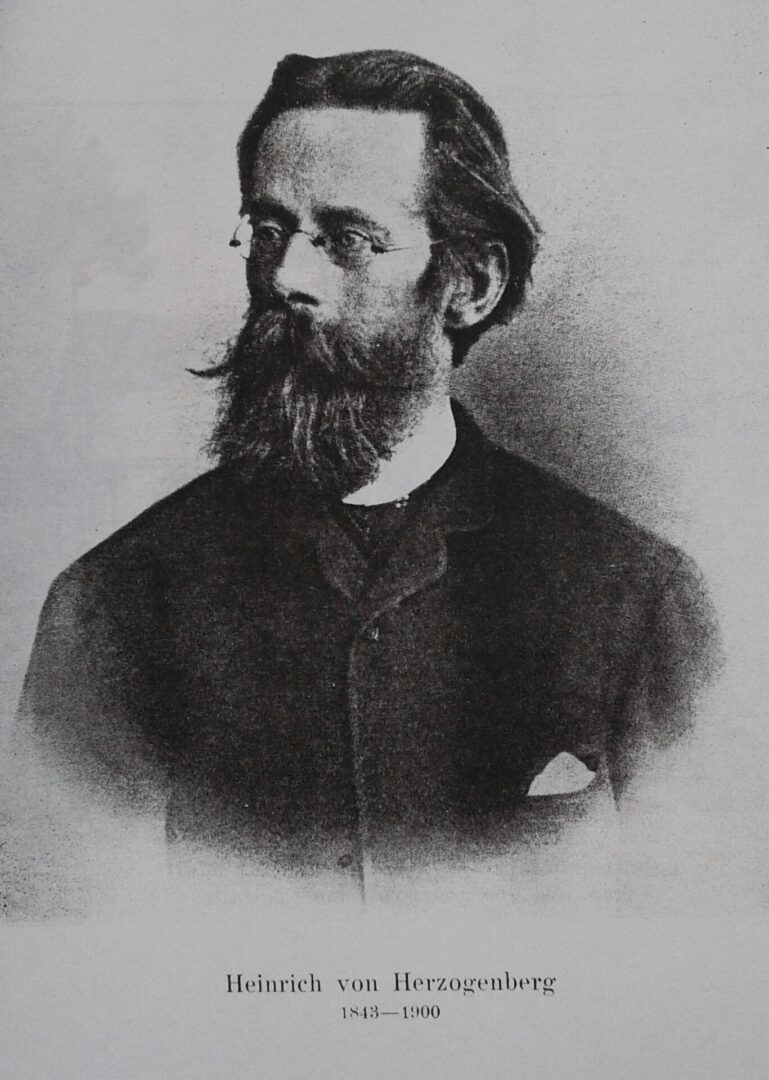

FRIENDS OF BRAHMS

BACKGROUND

The beginning was simple, but took me by surprise. I love Brahms’s music and when I came across Paul Holmes’s pictorial biography on a weekend visit to Columbus, Ohio, I bought it out of curiosity—but returning home to Chicago, merging again with the straight line of my life, I shelved the book and forgot my purchase. It wasn’t until a few years later, coming across Hans Gal’s book on Brahms, that I was reminded of the Holmes. I am a writer, and turning the pages of the Gal I realized that if I bought the book it would be with the intention of writing a book on Brahms myself. I realized simultaneously that if I didn’t buy the book then, I would be back for it at a later date.

The decision to write the book had been as unconscious as the preparation was not. I started by reading everything I could find on the man, devouring book after book until I could predict what I would read on the next page. I soon realized that the Schumanns were a large part of the story and they became subjects of the novel no less than Brahms, leading me to book after book on the Schumanns. There was no understanding Brahms without understanding his relationship with Clara (with whom he fell in love) and Robert (who became his mentor). No less could I avoid appearances by Mendelssohn, Chopin, Liszt, and Wagner among many others when their lives intersected—and no less historic events such as the Dresden uprising, the rise of Bismarck, and the emergence of Germany as a nation when they affected their lives. Ironically, Clara became the central character, threading the narrative from beginning to end more than either Robert or Brahms.

I did not know what direction the book would take when I started, but I knew I did not want to write the kind of book that propelled fictitious events into the public consciousness by exploiting the celebrity of its characters. There was no need. The historical record was dramatic enough to require no embellishment. I wrote what I knew, what I didn’t know I researched, what was beyond research I imagined.

EXCERPTS

One

The rule in Paris was to play first at soirees, and if and when the newspapers mentioned you to follow up with a concert. Her uncle arranged for invitations to soirees and the first at which Clara played, the Princess Vandamore’s, was notable as much for what happened as what did not. The chambers were upholstered, hung with tapestries and portraits, stuffed with porcelain, figurines, vases, cups, and stuffed animals and birds; dogs had the run of the rooms as did parrots and canaries—as, to Clara’s delight, did a monkey, with whom she shook hands, though Wieck warned that she could not trust such an animal not to bite—alongside princes, ambassadors, and priests arrayed in their finest. Wieck shook his head in disbelief; the French were children pretending to be adults; how Bonaparte had conquered Europe he would never fathom.

A young man approached the piano for which Wieck was relieved, more comfortable listening to music than making conversation, particularly in French. The man was short, stooped, and frail, his eyes were heavylidded, and the long fair hair covering his ears was exquisitely combed. He smiled, appearing to enjoy himself, but looked beyond the walls and once he sat at the piano he appeared beyond the weal of the world himself. Wieck, more concerned with seating himself comfortably, paid little attention until the man began to play, one note in the high treble, so clear and commanding that Wieck became still. A configuration followed, more single notes, first descending, then ascending, but what a configuration! With an uncanny use of the pedal he had blended the individual notes into one great blooming undulating chord.

Clara gripped his wrist with a whisper. “Chopin!”

Two

He sighed, sitting again at the piano. Willy wouldn’t be back until late in the evening and he was faced with the prospect of the long day ahead. He had work to do on the Zeitschrift and the Fantasiestucke he was writing for Robena, but he sat at the piano instead, doing nothing—or so it appeared, but something was spinning in his head that he needed to let out and he could let it out only on the piano.

He couldn’t explain how it worked: had he not pined for Clara there would have been nothing to release; had he not sat motionless at the piano there would have been no conduit for release. He couldn’t have said how long he sat, but something congealed in the time, the red blood, the hard bone, of the new composition, a strident melody, roiling harmony, interspersed with tender interludes, pulled from the collision of the thunder outside, the purr of the rain, and the noise in his head. He held his hands over the keys and under them the landscape of his nerves, blood, and bones sprang to life, little kingdoms growing under his fingers.

Three

On March 7, 1897, a shrunken Johannes Brahms, suffering from cancer of the liver, attended a performance in Vienna of his Fourth Symphony. The symphony glides so smoothly into its first theme that the listener finds himself deep in its wake before he realizes it has even begun.

The second movement showcases a plaintive melody hovering around a single note like a hopeless lover. A friend had said that only Brahms could have written that symphony, and even Brahms had had recourse to certain locked chambers of his soul for the first time—but he had finally run out of locked chambers.

At the end of each movement the conductor turned to Brahms’s box to acknowledge the composer, the audience stood, and the composer stood to acknowledge the downpour of applause, knowing the symphony would not otherwise recommence.

With the conclusion of the symphony, the downpour swelled to a monsoon, all eyes turned to the tiny man, hollows in the back of his neck, skin discolored to bronze, trembling with tears, the auditorium awash with light and color in his blurry eyes.

Twenty minutes later the emaciated old composer still stood, the audience still applauded.

He was tired, but remained standing, clinging to the rail, buoyed by the love in the hall, wishing no more to sit or to leave than they, his lovely Viennese, wished to let him go, their eyes no less damp than his own, cheeks no less bright, manly beards aglitter with tears like diamonds, all of them knowing it was the last time they would be seeing one another.

He died less than a month later, but what remained—the residue, the essence, distillate of his life, gold from straw—remains impervious to fang and claw, at once the heart of the riddle of life and medicine for the heart.